Keats, above all his contemporaries, is our contemporary. He has become and continues to be the most compelling of the Romantics. His short life, as moving a story as it is, might well have become the pulp of sentimental myth. He himself rescues his story: his “Letters” are perhaps the most interesting and beautiful ever written, while a strong selection of his poems makes him into one of the greatest of poets, whose elevation of the lyric form into tragic and sublime status has had lasting influence.

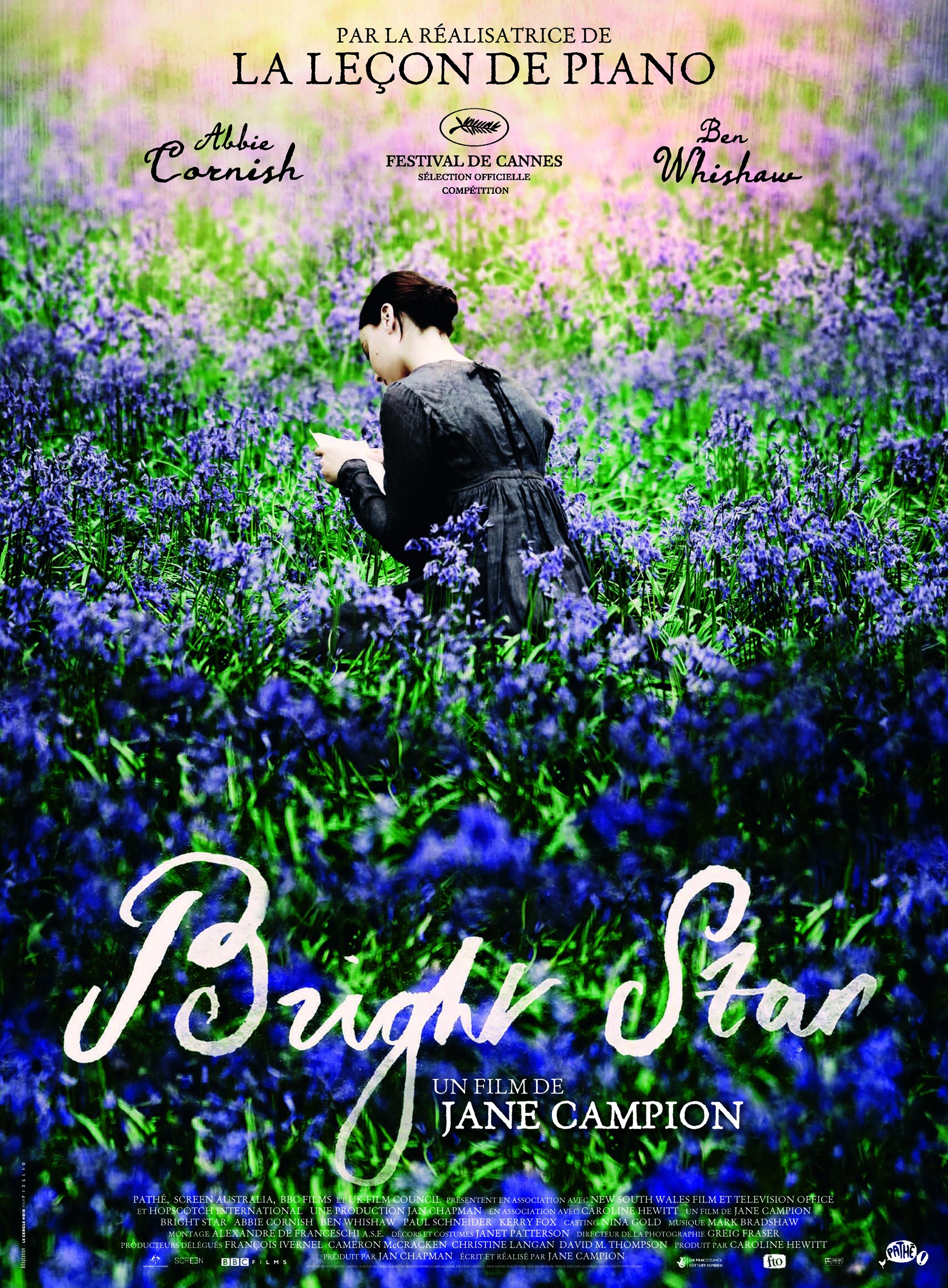

The film “Bright Star” (find here a summary Bright Star film) named after the poem John Keats supposedly wrote for Fanny Brawne, is a well of information for whoever is passionate about this Romantic poet, his ever-burning passion for Fanny, his love letters and his view on poetry.

In his February-May 1819 journal-letter to his brother George, the nineteenth-century English Romantic poet John Keats remarks that “they are very shallow people who take every thing literal. A Man’s life of any worth is a continual allegory—and very few eyes can see the Mystery of his life—a life the like scriptures, figurative—.”

Keats’s relationship with Fanny releases his best and now immortal work, ranging from “The Eve of St Agnes,” “Lamia,” and “La Belle Dame sans Merci” to the magnificent Odes and “The Fall of Hyperion,” and including any number of beautiful sonnets, among them “Bright Star.” Fanny becomes not only an inspiration but, for Keats, the signature of life itself, since, from the first realization of their feelings for each other, Keats knows he is not well.

In the last moments of the film Fanny cuts her hair in an act of mourning, dons black attire, and walks the snowy paths outside that Keats had walked many times in life. It is there that she recites the love sonnet he had written for her, “Bright Star”, as she grieves the death of her lover.

The much-reviewed scene in which the would-be lovers, in a bedroom, are speaking back and forth lines from Keats’s newly composed ballad ‘La Belle Dame…’ surely qualifies as flesh-made-word love-making. The scene gorgeously represents what poetry as well as love are about — the spiritual inseparable from the carnal.”

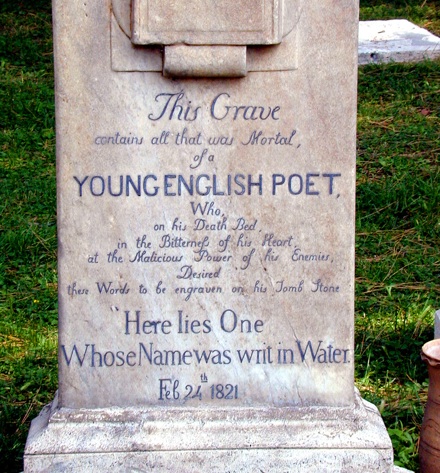

John Keats’s Tombstone, Rome, Italy. Photo by Widening Gyre 94 on Flickr

John Keats’s Tombstone, Rome, Italy. Photo by Widening Gyre 94 on Flickr

At the time, Keats’s positive reputation as a poet was limited to his friends, while his standing with his critics was less than zero. After his death in Rome, in 1821, at age twenty-five, the popular opinion was that he had been killed by his critics, “snuffed out by an article,” as Byron puts it. Or, as the words on his famous gravestone put it: “This Grave contains all that was Mortal of a Young English Poet who on his Death Bed in the Bitterness of His Heart at the Malicious Power of his Enemies Desired these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone ‘HERE LIES ONE WHOSE NAME WAS WRIT IN WATER.’ ” To Shelley, in his pastoral elegy “Adonais,” Keats had become “Like a pale flower by some maiden cherished,” a flower unable to withstand, because of his physical and psychological condition, the cold harsh winds of criticism.

One of the most poignant moments in the film occurs when Keats places his very mortal hand against his bedroom wall, knowing that Fanny, on the other side of the separation, is placing her hand, like a rhyme, against his. So much of the power of the Keats-Brawne love story finds its source in the near-yet-far fact that they are direct neighbors, sharing what is now ironically known as the Keats House. In 1818-19, it was a double-house owned by Charles Dilke and Charles Brown, both friends of Keats. When the two men built the house it was one of the first full-time residences in the London suburb of Hampstead, which up until the early nineteenth century tended to be scattered small farms or summer property. Dilke has moved back to London to be near his son in school and has rented his half to the widow Mrs. Brawne and her three children, the oldest of whom, at eighteen, is Fanny. Keats has moved in with Brown on the verso side of the house following the December death of his brother Tom. Everything flows from the accident of this intimate yet limiting domestic arrangement.

In profound ways, Charles Brown, Keats’s closest friend, sometime collaborator, and on-going benefactor, is not only the complicating third in the love story, he is its dark energy. Brown and Fanny—also neighbors—have a sexually charged and antagonistic relationship. When it comes to Keats, Fanny thinks Brown is a possessive, controlling presence; Brown thinks Fanny an undereducated fashion flirt.

The scene in which he admits to Fanny his betrayal of Keats by not traveling to Rome with and caring for his friend in his last hours is easily as riveting as the scene of Fanny’s final breakdown at the news of Keats’s death. As in classical tragedy, someone must be the bearer of the bad news and Brown becomes the messenger: his later admission of his failure regarding Keats becomes his recognition scene.

One of the most intimate early scenes of the relationship takes place over an impromptu poetry lesson, though Keats is suspicious of Brawne. When she asks for an introduction concerning “the craft of poetry,” Keats dismisses the notion: “Poetic craft is a carcass, a sham. If poetry doesn’t come as naturally as leaves to a tree, then it better not come at all.”

As the conversation continues, however, Brawne earns Keats’s trust, and he offers a more useful explanation: “A poem needs understanding through the senses. The point of diving in a lake is not immediately to swim to the shore; it’s to be in the lake, to luxuriate in the sensation of water. You do not work the lake out. It is an experience beyond thought. Poetry soothes and emboldens the soul to accept mystery.”

From that point on, Brawne develops an obsession with poetry—mostly Keats’s own poems—and occasionally recites favorite verses from memory. It is through Brawne that much of the poetry of the film reveals itself, either from her memory, or read to her by Keats.

Poems excerpted in the film include the book-length sequence Endymion, “When I Have Fears that I May Cease to Be,” “The Eve of St. Agnes, section XXIII, [Out went the taper as she hurried in],” “Ode to a Nightingale,” “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” and the title poem, “Bright Star,” which film director Campion depicts as having been written with Brawne as Keats’s muse, though the historical evidence is inconclusive.

As Andrew Motion notes in Keats: A Biography (which Campion credits as having inspired the film), there are two parallels between the poem and Brawne: the first is found in one of Keats’s love letters to Brawne (“I will imagine you Venus tonight and pray, pray, pray to your star like a Heathen. Your’s ever, fair Star.”), and the second is the fact that in 1819 she transcribed the poem in a book by Dante which Keats had given her. There are, however, poems that were definitely written to Brawne (“The day is gone…” and “I cry your mercy…”), and Motion points out that their form resembles that of the title poem.

Another of Keats’s works unmistakably written for Brawne is the poem “To Fanny,” the last known poem written by Keats. In it, the poet addresses doubts and suspicions about Fanny—a turn at the end of Keats’s life that Campion understandably leaves out of the film entirely.

“[‘To Fanny’] begins with a desperate challenge to the advice that [Keats] should avoid writing,” explains Motion, “describing ‘verse’ as an illness which ‘Physician Nature’ must cure by bleeding.”

Are there any scenes that struck you both for the content and for the way they were shot? For the photography? For the soundtrack? For the montage? For the framing? (inquadratura)

Do these questions help you? Why (not)?

These videos will help you acquire some basic language to anayse a film:

Listen to the interview to the main characters and the film director, what do they like about the poet and man John Keats?